03 Nov How to get, in three steps, from financial metrics to supply chain strategy

Running a company involves an ongoing evaluation of its business performance. Financial metrics are key to do this and are like a compass, showing the possible strategic avenues. As they form the beacons for the company to stipulate the company’s course, there’re well-known by the management levels. Much less known, however, is that they are equally good handles for agreeing on the supply chain strategy.

A practical framework

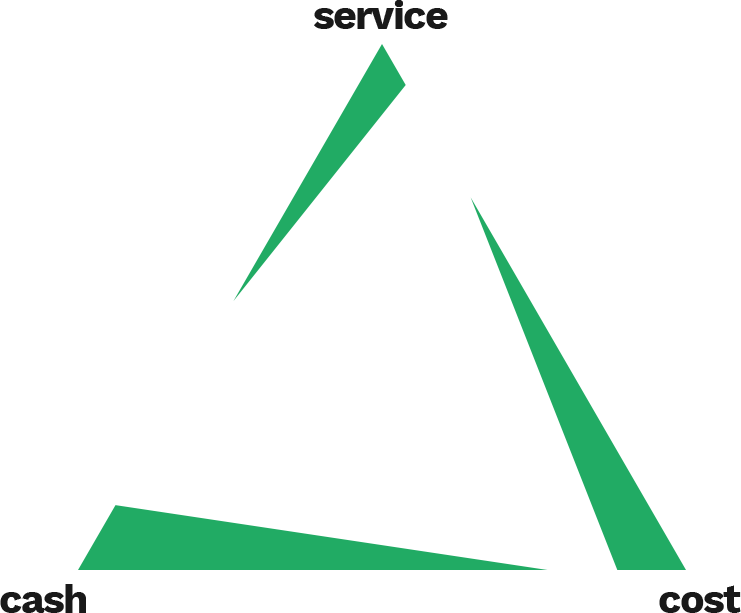

To convert financial metrics into supply chain strategy I’ve developed the Supply Chain Triangle of service, cash and cost. Basically, the Supply Chain Triangle concept captures the idea that organizations deliver different types of service to their customers, which come at a certain cost, and require a certain amount of inventory or, more generically, cash. Even more correct is to express ‘cash’ as ‘capital employed’ because, for good insights into their investments, organizations should make the sum of the working capital (inventory + accounts payable/receivable) and the fixed assets.

The Supply Chain Triangle reveals its true power in three steps:

Step 1: insight into the balancing act

A first step is to understand the balancing act between the three sides of the triangle, service, cost and cash (capital employed), as it is actually the essence of supply chain management. Decisions in one corner of the triangle almost automatically impact the other corners. For example, a broader product portfolio will add value for the customer and will help increase market share but, on the other hand, it will require more inventory.

Step 2: understand the link with finance

We can link the Supply Chain Triangle fully to financials. Taking the investor’s perspective will also be the solution to avoid massive tension in the triangle. Service is a driver of net sales, but investors are not only concerned about the top-line. They’re also interested in a metric like EBIT, which combines the service and cost aspect. And it does not stop there. If an investor compares two companies, both with € 100 million of EBIT, than the company with €50 million of capital employed will be more attractive to invest in than the one with €75 million of capital employed. In the end, investors are looking at the EBIT generated over the capital employed (cash-side). This is expressed by the financial metric ‘ROCE’ or Return on Capital Employed.

Step 3: make the conversion to strategy

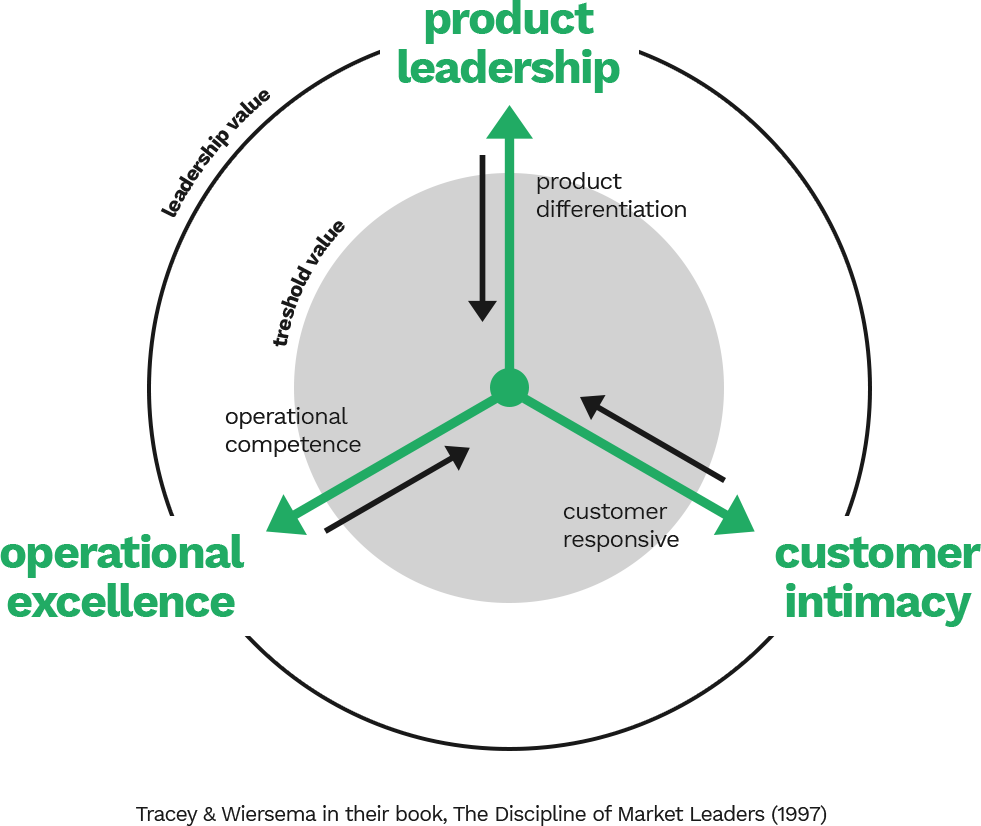

ROCE is more than just a financial metric, it is the ultimate objective. Different supply chain strategies can be seen as various routes to deliver the same shareholder value, using ROCE to measure this. Let’s make it more concrete with an example comparing operational excellence players with product leaders.

An operational excellence (opex) player will work at the lowest possible cost and with a minimal EBIT. The lower EBIT will be matched with a lower capital employed. To guarantee the lowest cost, an opex player will reduce complexity. He will not have a long tail in his supply chain but focuses, instead, on the big volumes. As a result he will have lower inventory and lower total assets or, in short, a lower capital employed.

A product leader will deliver high-end products into high-end niches. His products are more complex. He will need to work with niche suppliers. As a result the product leader will have a higher inventory. He will not be able to use his assets at the same efficiency, as demand is unpredictable, and because of a much higher rate of innovation. As a result he will also have a higher capital employed.

Investors feel comfortable with an opex player having a lower EBIT, as long as he employs less capital. And, vice versa, a product leader can have a higher capital employed, as long as he also generates a higher EBIT.

Paving the strategical path

Different strategies results in specific targets for supply chain metrics, e.g. for working capital. It also means that different strategies lead to other supply chains. In essence, you can reveal and assess a company strategy, and thus the supply chain strategy, by looking at the key financial metrics. Or, vice versa, with a good insight into the/(or: with a good knowledge of) financial metrics, you can more easily take strategic decisions. And isn’t that what we are all after?